1. Everything is a story. My friend Max Shatner believes that success in life depends on our ability to tell a good story. He even wrote a book about the success of the Jewish people, as based on their ability to tell stories (I would share it with you, but it’s in Hebrew). I agree with Max. I often tell my classes that “Everything is a story”.

2

In my class on sixties music, I tell a lot of stories. I talk about the Beatles. Who really wrote a given song? Was it Paul or John? Both of these highly talented musicians sometimes told two different stories about how and why a certain song was written.

3

There is a story the Beatles tell of their early days, of travelling across Liverpool, to learn to play the B7th chord on the guitar. Should we believe it? Who cares? It’s a great story.

4

5

Religions are based on storytelling. The Tower of Babel is a great tale indeed. None of us were there to watch it unfold. But a moving eternal story in any event.

6

7

And what about science? Did the apple really fall on Newton’s head? Did Archimedes jump naked out of that bathtub? How was fire really discovered? Was Einstein’s wife behind the theory of relativity? And did Kellogg invent pop-tarts?

8

9

Scientists tell stories all the time, whether or not they admit it. Some people think that science helps us know things. I don’t think that we can really know anything for sure. Perhaps Kant says we can, but I say we can’t. I think that scientists are storytellers. Just like everyone else.

10

11

2. The Medium May or May not be the Message but it is Sure is Important in Storytelling Many a medium can be used to bring a story to life. You can write a story, play or novel, act it out in the theater, compose lyrics and a tune, make up a joke, paint a painting, film a movie, deliver a presentation, or simply tell your story.

12

13

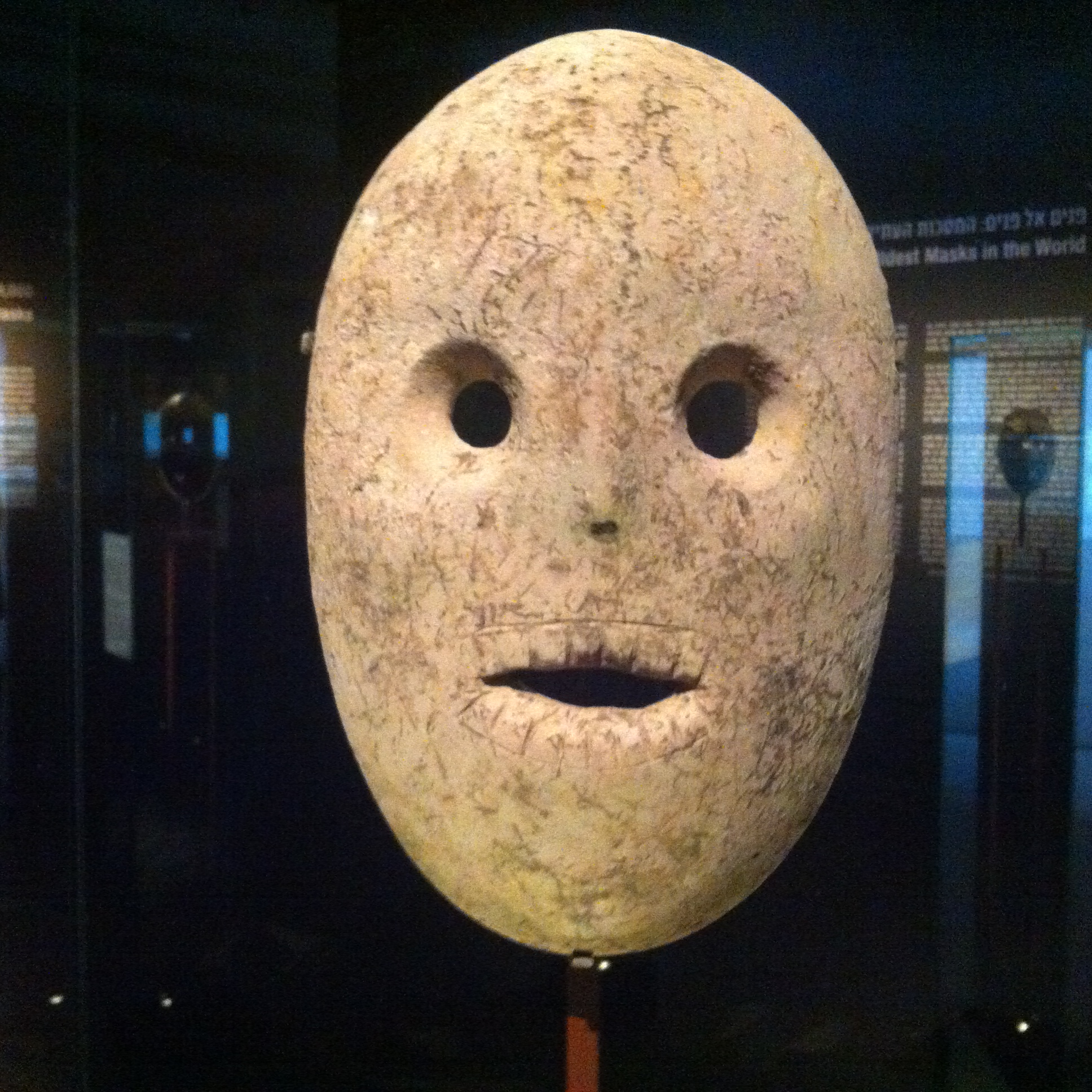

Thousands of years ago (9,000 we are told), peoples of a lost ancient civilization made masks that survive to this day. They have bits of ancient hair, meaning that they were worn for some purpose. Maybe storytelling, we just don’t know.

14

The particular medium that we use to tell the story has an effect on how the story is told, how it is communicated, which senses we use to perceive it, and how we feel about it. Didn’t Marshall MacLuhan say “The Medium is the Message?”

16

You can either pick the medium that best suits the story, in your opinion. Or you can choose the medium you feel most proficient at.

Either way, the success and very nature of a story depends on the medium through which it is communicated.

17

3. It is about you.

A few years ago Hagai Cohen and I came up with an idea for a social activity for consenting adults. We called it “Story, Spirits, and Song”. Each person in the group tells a personal story (no more than five minutes long), we drink a toast, and then pick a song that reflects the story that we all sing together. Until each person in the group has told a story.

18

When we first started the project, folks could tell any story. But time and again, we discovered that the more personal the story, the more fun it was to listen to and enjoy. We now insist that the stories be true, poignant, personal to the extreme, something that really happened. I have cried more than once listening to friends and strangers tell real stories from their own lives.

19

The secret? Empathy. Empathy with the characters. Empathy with the storyteller. How do you achieve that? Here are ten ways

20

21

The trick of course is to tell the story with authenticity, integrity, emotion. When that happens, we can all identify with it, feel empathy, emote our guts out, cry, laugh.

Real, personal stories are winners when told with integrity and feeling, in an authentic manner.

22

4. It’s not about you. Stories are a team sport. They are told to an audience. A good story is not good if the storyteller is the only one who enjoys it. It needs the interaction with the audience. The audience has to be moved by a story, wowed, seduced, brought to laughter and tears, transported back in time, forward in time. Good stories evoke memories, thoughts, fears, hopes, belief, doubt, resentment, passion. And love.

23

5. Even When a Story Doesn’t Appear to be about You, it Still is

Sometimes your story is related to your work or profession. It could be a pep talk you give your team, a presentation you give your colleagues, a presentation to a class or a conference, or a pitch to a potential investor in your company or start up.

The audience looks for cues in any story, whether written or presented orally. Are you fully behind what you say? Are you excited by it? Is there something personal about it that you can share?

24

When scientists apply for academic positions, they are usually asked to present an oral seminar. Why? Why don’t they just submit a written paper summarizing their research and send it to the department to read? Why are there so many conventions and conferences around the world? Even when a subject is professional, the audience is still coming to see ‘you’, the person who is telling the story.

25

Many stories are about someone or something else. A story might be something that you have ‘made up’, something from your imagination. It might be a song about love and regret, or a story you make up for your children about a duck who couldn’t find its glasses.

But when you make up a story, it’s still a reflection of your thoughts, your memories, your education, your beliefs, and the audience you wish to address.

26

6. Answering the questions

People, by nature, ask questions. They will want to know things, such as…

Who are you? What do you do? What is your goal, your dream? Where did it all start? How will you achieve it? Where did you come from? Where are you now? Where are you going?

27

Here are some of the questions the audience (or investors) will be asking.

How did you come up with the idea? How will you achieve it? How will you change the world? How does your product work? So what?

Why should I listen to you? Who cares? Why should I buy what you have to sell?

28

6. Classic Storytelling

In a classic story. the character is confronted with a problem, a challenge, a crisis. He or she is tested. Often the crisis is related to a flaw in the character of the hero. Sometimes the crisis comes out of nowhere, as it often does in real life. In this case, the hero or heroine must muster up whatever she needs to overcome it.

29

The who in a classic story is the character and the adversaries. The what is the story line – what actually happens. The when is the time the story occurs, past, present or future. The where is the location (note that the where and the when often contribute to the atmosphere and setting of the story). The why can be the flaw in the hero’s character, the events that set the story in motion. The how is how the character deals with the challenge and overcomes it.

30

7. The structure of the story

Stories usually need a structure. You can start out by explaining in one sentence what the story is about. If your opening is captivating, the crowd will be captivated.

The main body of the story should follow some logical pattern. Otherwise you will confuse your audience.

31

The ending of the story can be as important or even more important than the story itself. What happens in the end? How is the challenge resolved? If it is mundane it will be less fun to read (if you don’t know the meaning and origin of the world of mundane, I suggest you look it up. It might lead you to a story!). On the other hand, if the ending is original, creative and surprising, children and elders will be delighted to enjoy it again and again.

Structure your story. Find a compelling opening sentence, and an amazing ending!

32

8. Naming Your Story and the Characters in it

What’s in a name? Everything, really. If you call your chief character Dorothy, it will be difficult to find her on the internet. It may remind people of another story. On the other hand, if your character is named Penny Popadiculous, you may be among the very first!

33

Naming your book provides a similar dilemma. If you name your story “My Dog”, it will be very difficult to access over the internet. A name such as “Franchise, my French Poodle” stands a much better chance.

So tip number eight is: Look for a special name for your character, and for the title to your story

34

9. Make Your Story Special

When you have finished writing the draft of your story, you might want to ask yourself, “What is special about my story? Does it have something that sets it apart from the millions of other stories in the world? Have I created a wonderful setting to my story, a mysterious atmosphere, a tale which is unique and memorable? If you wonder about the answer to this question, your readers will too.

35

Create a unique setting, atmosphere, experience. Make sure it sets itself apart from other books in at least one imporatant way.

36

Max Shatner wrote me, “Following the WH questions you describe, I would add another useful instrument – the “secret sauce” (in startups) or “magic wand” (in real life). This instrument may come in many forms. Its purpose is to help the hero achieve his goal. Both investors and movie fans love it. It is an answer to “with what”.

37

10. Learn the Tricks of the Trade

Each story medium has its own tricks. If you are giving an oral presentation, then there are lots of tricks you can use. One example is pausing before you say something important. There are many, many more.

38

If you are writing for children, you might consider using expert tricks of the trade such as repetition and onomatopoeic (words that imitate sounds, such as bang, whoom, and oink).

Try to get feedback from experts. Take courses. Read. Try your story out on an audience. Are they excited? If so, you should be too. If they suggest ideas, listen. Mentors and your potential audience can help you hone your story skills in any medium.

39

Published: Feb 14, 2015

Latest Revision: May 10, 2020

Ourboox Unique Identifier: OB-31619

Copyright © 2015

1 thought on “Mel’s Ten Tips on How to Tell a Good Story”